| From a homily by St Bede the Venerable, priest |

|---|

| From a homily by St Bede the Venerable, priest |

|---|

4324 William Flete ()

Joseph Ratzinger (who became Pope Benedict XV) wrote that Christianity “draws attention to the fact, and I quote, that the religious experience of the human race has continually been kindled at 'holy' places, where for some reason or other... the divine becomes particularly palpable to man".

This is certainly true of Lecceto, the holiest and most famous of Augustinian houses from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The call of Lecceto as a place of holiness was heard not only by Augustinians drawn there from many parts of Italy but also from France and from further abroad. One of the most noted foreign Augustinians to live there was William Flete, an Austin Friar (i.e., an Augustinian of England).

Lecceto

Most probably he did all his studies at Lincoln before being promoted to live and study at the Austin Friary at Cambridge University, with a view to obtaining the coveted magisterium, the degree of doctor of theology. William never used the surname "Flete" in any of his extant writings. In an original letter that has survived, he signed himself as frater guielmus de Anglia ("Brother William of England.") The earliest mention of the surname "Flete" occurs in the Registers of the Prior General, Matteo d'Ascoli on 8th September 1359. It is known that Flete had been ordained a priest some time before 29 February 1352, and graduated as bachelor of theology in 1355. Having cleared this hurdle, he would have proceeded as a matter of course without difficulty to the magisterium. He was ready to begin the final exercises leading to the degree in 1358. With the early Augustinian Order's emphasis on learning, this prospect was a glittering one. Academic life had an appeal all its own, masters of theology were a privileged class in the Order.

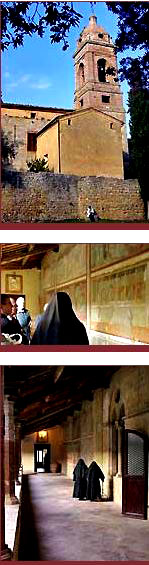

Photos (at right):

Picture 1: Church tower at Lecceto.

Picture 2: A nun explains a fresco at Lecceto.

Picture 3: A cloister corridor at Lecceto.

To renounce one's opportunity of graduating as a master was probably unheard of. To prefer instead to leave one’s homeland, family and friends and bury oneself in a secluded Italian hermitage was even more unusual, but then Flete was a most unusual friar. He certainly possessed some of the qualities attributed to an eccentric English academic. Sometime before 1358 he had begun to question the direction of his life as an Augustinian. There were Italian students at Cambridge and there can be little or no doubt that it was from some of them that he first heard of Lecceto and its history both ancient and contemporary.

At Lecceto the original eremitical (“hermit”) spirit of the Order was preserved. If one was to live out literally one's calling as a hermit of St Augustine, then Lecceto was the most suitable place to do it. Of all the original hermitages in the Augustinian tradition, it alone survived and carried on the false Augustinian myth falsely that Augustine had in person visited hermitages in Tuscany. As he reflected on this, Flete could not help contrasting it with what he saw around him. Something of a traffic jam had been building up. Places at the university were strictly limited, and, as might be expected, students from other provinces, mostly Italian, were being ousted from their rightful place in the queue. Resentment naturally built up. It was an unfortunate and wholly undesirable situation, but in the circumstances almost inevitable, since learning and academic success were so highly valued in the Order ever since the time when Giles of Rome O.S.A. (Egidio da Roma) was Prior General.

William Flete had become thoroughly disenchanted with the scrambling for places and with the worship paid to intellectualism. Many years later he was to write back to England from Lecceto and say: "This great learning is the ruin of the Church of God and of all religious orders". He was not alone in thinking as he did. Two other Austin Friars, John Doddington and William Pigot, took the same road. All three left England on 17th July 1359, bound for Lecceto. Flete had resigned his chair at Cambridge University some twelve months earlier; by that time he was a very mature man and an authority on the spiritual life. He was already the author of an excellent study of the problem of temptation with special reference to faith. Flete's approach is very interesting. It is personal, philosophical, psychological, theological and exceedingly balanced.

Lecceto

Writing home twenty years later, he gave more than a hint of what seems to have been a continuing struggle not to give up. God, as he saw it, had called him, as he had called Abraham, to leave his father's house, country and friends, and go into a distant country, there to spend the rest of his days. He had come to Lecceto in search of the authentic Augustinian way of life, the life of a hermit within a community setting. The physical setting was ideal. The precincts of the monastery were virtually isolated from the outside world by the dense wood which surrounded it. The horarium (daily timetable) of the community allowed ample time for anyone who wanted to live a quasi-solitary life. Flete's favourite haunt was a cave or grotto, of which there are still examples, hidden in the woods. The praise lavished on Flete by contemporaries, the tributes to his great learning, his deep spirituality, his wisdom as a counsellor and a man of penance is not shared by any other of the followers of St Catherine of Siena.

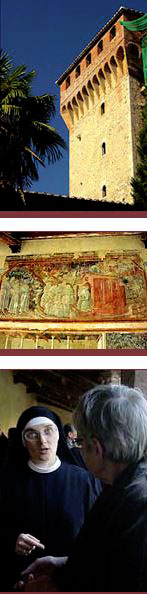

Photos (at left):

Picture 1: Famous square tower at Lecceto.

Picture 2: An ancient fresco at Lecceto.

Picture 3: A nun guides a visitor at Lecceto.

There is indeed good reason for thinking that he was the formative influence on the development of her theological thought. But that is a subject that lies well beyond our present compass. Here we have to note how contemporaries singled out for mention his quasi-solitary mode of life at Lecceto. Evidently Flete practised, as far as community life allowed, the vocation of a hermit. There were bound to be problems vis-a-vis the community, and the Lecceto Prior’s patience, tact and understanding must have been put to the test by Flete's singular way of life. But was it so very singular after all? Apparently Flete carved out his own grotto in the woods. Yet can it be assumed that he was a lone pioneer in this respect? Indeed, other caves or grottoes have been found not only at Lecceto but also in other Augustinian foundations, for instance at Fano near the Adriatic. In other words, Flete was not an innovator but rather a traditionalist in his following a quasi-solitary mode of life at Lecceto.

He was primarily a contemplative, yet also gained a reputation for possessing great learning. He was referred to as il baccelliere ("the bachelor") because of his bachelor's degree in theology from Cambridge. Even St Catherine of Siena called him thus. From sworn statements made in 1411 during the canonisation process of Catherine of Siena, it is known that William and Catherine first met at Lecceto as early as 1368, when the crucial period of Catherine's spiritual development occurred in 1367-1374. Nobody in Siena was at all as qualified as William to understand and guide her spiritual development at that time, during which her spiritual self-confidence blossomed and she began her life's work of devoting all her energy to the reform of the Church.

William was the only really competent theologian, and a master of the spiritual life as well, with whom Catherine had regular dialogue during those fateful growth years of her spiritual life. He willingly recognised her as one whose spirituality exceeded his own. There is a reputable historical source that attributes Flete's exclaiming, "The Holy Spirit is truly in her." Proof of Flete's influence on Catherine exists in the twenty-one extant letters of spiritual instruction (and she may have written more letters of this nature) that she dictated between 1367 and 1374. These letters are filled with pure Augustinianism, of which he must have been the source. (Another 382 of her letters are still extant.) Flete himself was the recipient of at least six letters from Catherine, addressing them to reverendissimo ("the most reverend"), a title she used for only one other person - Pope Gregory XI.

Lecceto

But William's influence was not confined solely to the devout. He won over hardened sinners, desperadoes like Nanni di ser Vanni, the terror of Siena in 1374; Catherine had failed to convert him. Nanni then surrendered to the authorities, receuived only two years' imprisonment, and gave one of his castles at Belarco to Catherine of Siena for use as a religious foundation.

Photos (at right):

Picture 1: The outer cloister at Lecceto.

Picture 2: A visiting Italian Augustinian friar at Lecceto.

Picture 3: A cloister corridor at Lecceto.

It seems amazing that, on the only occasion Flete in all of his thirty years or so at Selva di Lago he ventured outside the place, it was to celebrate at Catherine's behest the Mass of Dedication in the Belcaro Castle. Perhaps - most surprising of all - Flete actively intervened for charitable and spiritual causes with successive governments of Siena and evidently had friends in the council chamber. For example, three of Catherine's brothers, Benincasa, Bartolomeo and Stefano, after the overthrow of their party's government, the Dodici, in 1368, were marked men. They probably owed their lives to Flete's intervention with the leaders of the new government for an amnesty for them. They were allowed to be exiled from Siena, and on 14th October 1370 applied for citizenship of Florence.

St Catherine of Siena had a high opinion of William Flete as a person of outstanding spirituality. It is proof of her confidence in him as a spiritual director that she entrusted solely to his care in 1375 the formation of a young Sienese, Matteo Forestani, whom she asked to be received as a postulant at Lecceto. But the most telling evidence of all is the fact that Catherine commissioned Flete to direct her group of disciples, the famiglia ("the family"), after her death. When Flete died at Lecceto c. 1390, his name was not even entered in the necrology of the monastery. Others with far less claim to fame were buried either in the church or the cloister, not in the communal cemetery. Not so Flete. Even though during his lifetime he lived virtually a separate life, in the sense that a cave not a cell within the enclosure was his favourite abode, in death he shared the lot of the ordinary friar. One possible theory for the omission of reference to William Flete in the Lecceto community necrology and for a very ordinary burial has been proposed by scholars of Augustinian spirituality and history, including Fr Aubrey Gwynn S.J. over seventy years ago.

Was there some tension between those at Lecceto who lived away from the community in caves and hermitages and those who resided within the confines of the monastery? There does seem to have been some tension when, for example, the eremites apparently were reluctant to assist the community routine by being bound to the clock and to a timetable for celebrating scheduled Masses in the chapel of the Lecceto monastery. The charism of Augustinian community life included service to the Augustinian community, and those who were not eremitically inclined could have regarded an eremite’s inadequate desire or reluctance to be involved in community tasks as a spiritual imperfection.

Could this reluctance have been the case with William Flete? This certainly appears so in a letter from St Catherine of Siena (known as her Letter 77) to William. At the end of the letter, as was customary for Catherine, some words of practical advice were added to the mystical instructions. She previously had written a very practical admonition to Flete and his fellow hermits on the need of obedience to their religious superior in all community duties. Her letter stated, “I say to you in the name of Christ crucified that whenever in the week the [Augustinian] Prior may wish you to say Mass in the convent, and as often as you see that it is his will, I wish all of you to say it. If you lose your consolations, you will not lose the state of grace; rather will you acquire grace, since you lose your own will."

Lecceto

To counterbalance this possibility somewhat, however, there is at least one factor: if William Flete showed himself too unwilling to leave his hermitage for the good of souls, it is well to remember that he had struggled for long years against foul temptations, and had at last found peace among the solitude of the ilex-trees in the Lecceto woods. Hence it is against this somewhat conflicting and perplexing background that we can best appreciate Flete's teaching on Augustinian life. His reflections are contained in three remarkable – indeed, unique - letters which he wrote under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, so he says, to the brethren in England in 1380. The first is addressed to all the fathers and brothers of the Augustinian Province in England; the second to the masters of theology; the third to the Augustinian Provincial, Henry Teesdale O.S.A.

Like his treatise on the remedies against temptations, these letters show that Flete shared with the leaders of the English school of mystics the qualities noted by Felix Vernet: "love of tradition, clear-sighted precision, common sense, strongly individual personality". There is also something in Flete's three letters which is worth noting, if only for the light it throws on the man's character and what it cost him to leave England and to persevere at Lecceto. One can see that he loved his family, friends and country so deeply that even to think about them was almost enough to make him give up his self-imposed exile at Lecceto. Flete points out that Augustinians would stand or fall by their observance or otherwise of the Rule of Augustine. The Rule is a mirror and Augustine will hold it up to us when we come to be judged. And so at the very outset of his first letter he quotes the famous opening words of the Rule of Augustine, the rule of charity. But in doing so he quotes a classic phrase from Gregory the Great: "Note the words, and grasp their significance". Those words of the Rule mean that there should be no discord in the province or in a convent or, among the brethren themselves. "Let there be the one spirit, the one soul in God".

The harmony existing among the brethren should be of the highest kind and impervious to assaults. This oneness is expressed at the deepest level at and by the community celebration of the liturgy of the hours, the divine office. All the community should participate, in so far as this is possible, and with the greatest possible effort recite the office clearly, slowly and devoutly. In stressing the importance of our saying the office with dignity and reverence, Flete is simply echoing directives of two earlier Priors General, William of Cremona O.S.A. (Guglielmo da Cremona) and Gregory of Rimini O.S.A. (Gregorio da Rimini). It is from these two generals that Flete takes his cue when referring to yet another pillar of community life, namely, the practice of religious poverty - often a much-debated issue for the Augustinians and the other mendicant orders.. He lays very great emphasis on the importance of the common life. Quoting the, Rule of Augustine which says "do not call anything your own", he adds: "the servant of God ought not regard anything as his own ... his sole delight should be in Christ crucified". The friars must rise above earthly things and fix their minds on heaven, for "our heart is restless, Lord, until it rests in you".

The public chapel of the Augustinian Nun's eremo at Lecetto

The eremitical (“hermit”) aspect of Augustinian life looms large in Flete's three letters. This is only to be expected. Apart altogether from his own rather peculiar mode of life at Lecceto, for him as indeed for others, including men who held the highest position in the Order, the Augustinian roots are eremitical. The Order would not be true to itself if the friars were to disown or feel embarrassed about its ancestry. However, Flete did accept that the life of the Augustinian Order was concentrated almost wholly in areas of population, right in the middle of the market square as well as in university centres. None the less, the friars should conduct themselves as if they were living in the desert. The title of Order of the Hermits of St Augustine, far from being a source of embarrassment for the friars, ought to be their greatest boast. Not all his contemporaries by any means would have agreed with him; but friars of distinction like Jordan of Saxony O.S.A. fully agreed with him in seeking to uphold the traditions of the early fathers of the Order.

Flete was not asking that all or for that matter anyone else should do as he did, i.e., bury themselves in the woods. In appealing to the title of the Order, he was protesting out of a sense of duty to the Order against a practice that had crept in and which was bad: friars wandering about for no good purpose on the slightest pretext, unable to stay in their cells, more at home in the houses of seculars than in their own communities, swarming all over the place. He deemed this to be so unfair to the laity, ant to be a scandal into the bargain. Flete was not exaggerating. More than one Prior General had sternly warned against this gadding about. In England the author of the celebrated allegorical poem, Piers Plowman, compared the friars to fiddlers going up and down the street and knocking at one door after another. What is the result of all this, asks Flete. Community life suffers and inevitably the obligatio chori (the “obligations of Choir”, i.e., presence in the chapel) becomes a dead letter.

Aerial view of the eremo (hermitage) in the pine forests of Lecceto

On balance, Flete upheld the primacy of the eremitical or contemplative nature of the Order as against the active or friar aspect, not because this was the common teaching of the theological schools as represented, for example, by St Thomas Aquinas, but precisely because in point of time the Augustinians were hermits before they became friars. Flete fully recognised the importance and necessity of the active apostolate, yet he also recognised the need for control and balance. He believed personally that the best contribution that he could make to the salvation of souls was the indoor apostolate, that is, the life of prayer and penance, spiritual direction and counselling. Such is Flete's summing up of the religious life. For him the essential aspect was charity, social charity. This must first of all be demonstrated in relations between the secular clergy and the religious orders, and between the orders themselves. In highlighting hospitality as a crucial, indeed, the crucial proof of charity, Flete no doubt had in mind his own experience on the road to Italy twenty years earlier.

His views are also in line with a decree of the Augustinian General Chapter of 1287, which was later embodied in the Augustinian Constitutions of 1290; but he goes well beyond the dry, precise form of the legislator. He said that Augustinians should delight in showing hospitality and in welcoming visitors as if Christ himself were that guest. It is thought that William Flete died at his beloved Lecceto in about the year 1390, a decade after the death of Catherine of Siena on 29th April 1380. After an unconscionable delay, she was canonised a saint on 29th June 1461, and in 1970 Pope Paul VI declared her a Doctor of the Church. As to William Flete's canonisation, apparently nothing was done about it at Lecceto, where even his grave was never marked. (As mentioned above, both these matters could possibly have been a consequence of tension at Lecceto between the regularly resident community members and those community members who lived much of the time afield in isolated hermitages.) Indeed, William Flete was probably the last person who would want to have been canonised a saint.

The above material is drawn from the writings of the late Rev. Dr Michael Benedict Hackett O.S.A.. After an illustrious academic career in ecclesiastical history, he died in England in March 2005.

Brown, Jennifer N. Fruit of the Orchard: Reading Catherine of Siena in Late Medieval and Early Modern England. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019. Pp. xi, 312 + 4 ill. ISBN 978-1-4875 0407-6 (hardcover) $75.

Jennifer Brown’s apt title refers to the Orcherd of Syon, the English translation of Catherine of Siena’s Libro di divina dottrina or Dialogo, and to the ways in which different readers in England plucked fruit from this or that aspect of Catherine’s texts and hagiography. Among Continental saints whose cults were exported to England, Catherine is usually upstaged by the much more prominent Birgitta of Sweden, but Brown’s study of the reception of Catherine’s writings and texts about Catherine in England seeks to show that there was indeed an “English Catherine of Siena,” (205) and that Catherine and her texts served as a spiritual model for several different strands of English devotional culture in late medieval and early modern England. In order to trace the transmission of Catherine’s texts and reputation, Brown focuses on the particularities of manuscripts and early printed books for what they reveal about the tensions and complications of English devotional culture during a time of great ferment and change. Each chapter focuses on one particular text or textual situation, beginning in chapters 1 and 2 with the roles played in introducing Catherine to England and shaping her reception there by two important members of her circle, both with connections in England. Brown traces the key role of Catherine’s close follower Stefano (here “Stephen”) Maconi, master general of the Carthusian Order, in the diffusion of Catheriniana from the Charterhouse of Sheen and the creation of a model for devotion to Catherine in terms that pre-empted concerns about her orthodoxy—important given the English church’s suspicion of female visionaries and vernacular texts. And she demonstrates how the Documento spirituale of the English Augustinian William Flete, a member of the Augustinian community at Lecceto near Siena and one of Catherine’s strongest supporters, circulated in England as The Cleannesse of Sowle and was attributed incorrectly to Catherine herself. Catherine’s writings fit into a genre of contemplative literature in which Flete was already well-known, and so her connection to Flete in effect prepared a space for her in English devotional culture. 286 book reviews T he variety of ways in which such shorter texts shaped Catherine’s reception in England is even more dramatically evident in chapter 3, in which Brown traces the complex web of interconnections and associations—as well as interesting misattributions—among texts by and about Catherine as they circulated in fifteenth-century miscellanies. Brown shows how Catherine’s persona and the meaning of her texts changed depending on the interests of the miscellanies’ compilers and/or readers and the forms in which her texts circulated. Catherine and her texts could be made “to accommodate different strands of late medieval English spirituality—as in turn pedantic, methodological, visionary, or mystical,” so that “who Catherine is and the purpose she serves is not inherent in the text itself, but rather in the pen of the compiler” (110). In chapter 4, Brown explores the role of the Bridgettine convent of Syon Abbey—the most important female religious community in fifteenth century England and a key centre for the production of devotional books—in shaping Catherine’s identity, especially through the translation of her Dialogo into Middle English (from a version in Latin) in the form of the Orcherd of Syon, the title of which placed Catherine securely within a Bridgettine context. Brown points to the translator’s preface, chapter divisions, and rubrics as not only guiding the reader through Catherine’s difficult text, but also encouraging a method of reading the work in smaller pieces, as if fruits picked from its trees—consistent with the guiding metaphor of the text as an orchard. T he last two chapters take Catherine into the Reformation period. Chapter 5 traces the dissemination of Raymond of Capua’s authoritative Legenda, translated into English as the Lyf of Katherin of Senis, through the 1492 edition by Wynken de Worde and inclusion of extracts of the Lyf in a collection of mystical texts printed by Henry Pepwell in 1521. Brown links the readership for these texts to a growing trend of private lay devotional reading in England and points out that it was thus primarily through the hagiography, and not through her own writings, that Catherine was known in England during the Reformation period. Her Conclusion traces the contradictory figures of Catherine as she was used in different ways by Protestants and recusant Catholics. Each of Brown’s chapters leads the reader through the complex details of textual transmission and provenance of specific manuscripts and printed editions that shaped the way Catherine was read in England. Brown convincingly ties these details to larger themes in English religion in this period, including issues of gender, tensions over authority and reform, and a growing culture of comptes rendus 287 lay reading and devotion. Moments of weakness occur where Brown departs from her methodological commitment to specificity. In chapter 2, even if one grants the (debatable) premise that Catherine’s approach to penance depends on Flete’s, it is not clear that the ideas that Catherine is supposed to have inherited from Flete are particularly “English.” In chapters 3 and 4, Brown sometimes slides confusingly between translations in a way that risks losing the distinctiveness and autonomy of the work of the different translators. In chapter 4, for instance, she blurs differences between Catherine’s original and its English translation to make Catherine seem unproblematically the author of both texts. Brown also notes that the Orcherd of Syon introduced chapter divisions in order to help the reader, but Italian manuscripts of the Dialogo in both Italian and Latin also have divisions into chapters. Does the Latin version on which the Orcherd was based not have such chapters, or are the chapter divisions in the Orcherd different from the ones in the Latin original? T hese issues aside, Fruit of the Orchard is a fascinating example of book history and establishes convincingly the importance of the reception of Catherine of Siena in later medieval and early modern England.

From the prayers of Saint Catherine of Siena: In

Mary was sown the Word of God (Propers for the Order of Preachers)

O Mary! Mary! Temple of the Trinity! O Mary,

bearer of the fire! Mary, minister of mercy! Mary, seedbed of the fruit! Mary,

redemptress of the human race—for the world was redeemed when in the Word your

own flesh suffered: Christ by his passion redeemed us; you, by your grief of

body and spirit.

O Mary, peaceful sea! Mary, giver of peace! Mary,

fertile soil! You, Mary, are the new-sprung plant from whom we have the

fragrant blossom, the Word, God's only-begotten Son, for in you, fertile soil,

was this Word sown. You are the soil and you are the plant. O Mary, chariot of

fire, you bore the fire hidden and veiled under the ashes of your humanness.

O Mary, vessel of humility! In you the light of

true knowledge thrives und burns. By this light you rose above yourself, and so

you were pleasing to the eternal Father, and he seized you and drew you to

himself, loving you with a special love. With this light and with the fire of

your charity and with the oil of your humility you drew his divinity to stoop

to come into you—though even before that he was drawn by the blazing fire of

his own boundless charity to come to us.

O Mary, because you had this light you were

prudent, not foolish. Your prudence made you want to find out from the angel

how what he had announced to you could be possible. Didn't you know that the

all-powerful God could do this? Of course, you did, without any doubt! Then why

did you say, "since I do not know man?" Not because you were lacking

in faith, but because of your deep humility, and your sense of your own unworthiness.

No, it was not because you doubted that God could do this. Mary, was it fear that

troubled you at the angel's word? If I ponder matter in the light, it doesn't

seem it was fear that troubled you, even though you showed some gesture of

wonder and some agitation. What, then, were you wondering at? At God's great

goodness, which you saw. And you were

stupefied when you looked at yourself and knew how unworthy you were of such

great grace. So you were overtaken by wonder and surprise at the consideration

of your own unworthiness and weakness and of God's unutterable grace. So, by

your prudent questioning you showed your deep humility. And, as I have said, it

was not fear you felt, but wonder at God's boundless goodness and charity

toward the lowliness smallness of your

virtue.

You, O Mary, have been made a book in which our

rule is written today. In you today is written the eternal Father' s wisdom; in

you today human strength and freedom are revealed. I say that our human dignity

revealed because if I look at you, Mary, I see that the Holy Spirit' s hand

written the Trinity in you by forming within you the incarnate Word, God

only-begotten Son. He has written for us the Father's wisdom, which thin Word

is; he has written power for us, because he was powerful enough to accomplish

this great mystery; and he has written for us his own—the Holy Spirit's—mercy,

for by divine grace and mercy alone was such a mystery ordained and

accomplished.

RESPONSORY See

Lk l: 48

Rejoice with me, all you who love the Lord; for

although I am only a little one, I have pleased the Most High, * and I have

given birth to God and man. All generations will call me blessed, for God has

looked kindly on a lowly servant, * and I have given birth to God and man.

Inviolata, integra, et casta es Maria

Author unknown, not later than the 15th

Century, sung by the Dominicans before the Vesper hymn on the Purification;

also used by the Dominicans at Compline (Byrne).

Inviolata, integra, et casta es Maria,

quae es effecta fulgida caeli porta.

O Mater alma Christi carissima,

suscipe pia laudum praeconia.

Te nunc flagitant devota corda et ora,

nostra ut pura pectora sint et corpora.

Tu per precata dulcisona,

nobis concedas veniam per saecula.

O benigna! O Regina! O Maria,

quae sola inviolata permansisti.

Inviolate, whole, and chaste art Thou, Mary,

who art become the gleaming gate of heaven.

O dearest nurturing Mother of Christ,

accept our pious prayers of praise.

That our hearts and bodies might be pure

our devout hearts and mouths now entreat.

By Your sweet-sounding prayers,

grant us forgiveness forever.

O blessed, O Queen, O Mary,

You alone have remained inviolate.

| A letter of St Maximilian Kolbe |

|---|

| From the memoirs of the secretary of St Jane Frances de Chantal |

|---|

PRIMO dierum omnium

This hymn is attributed to Pope St. Gregory the Great (540-604) and there is good reason to think he may have written it. The ancient preface to St. Columban's Altus prosator describes the arrival of St. Gregory's messengers from Rome bearing gifts and a set of hymns for the Liturgy of the Hours. In turn, St. Columban sent a set of hymns he had composed to St. Gregory. There has been considerable debate of late as to whether St. Gregory really did write the hymn or if he simply sent what was current in Rome at the time. Considerable evidence can be put forth for both positions.

This traditional winter-time Sunday Matins hymn is used in the Liturgia Horarum for the Sunday Office of the Readings of the first and third weeks of the Psalter during Ordinary Time. The hymn below is the complete hymn, whereas in the Liturgia Horarum only the first four verses are used along with a different concluding verse. In the Roman Breviary the hymn has been heavily modified and appears as Primo die, quo Trinitas.

PRIMO dierum omnium,

quo mundus exstat conditus

vel quo resurgens conditor

nos, morte victa, liberat.HAIL day! whereon the One in Three

first formed the earth by sure decree,

the day its Maker rose again,

and vanquished death, and burst our chain.Pulsis procul torporibus,

surgamus omnes ocius,

et nocte quaeramus pium,

sicut Prophetam novimus.Away with sleep and slothful ease!

We raise our hearts and bend our knees,

and early seek the Lord of all,

obedient to the Prophet's call:Nostras preces ut audiat

suamque dexteram porrigat,

et hic piatos sordibus 1

reddat polorum sedibus,That He may hearken to our prayer,

stretch forth His strong right arm to spare,

and every past offense forgiven,

restore us to our homes in heaven.Ut quique sacratissimo

huius diei tempore

horis quietis psallimus,

donis beatis muneret.Assembled here this holy day,

this holiest hour we raise the lay;

and O that He to whom we sing,

may now reward our offering!Iam nunc, Paterna claritas,

te postulamus affatim:

absit libido sordidans,

omnisque actus noxius.O Father of unclouded light,

keep us this day as in Thy sight,

in word and deed that we may be

from every touch of evil free.Ne foeda sit, vel lubrica

compago nostri corporis,

per quam averni ignibus

ipsi crememur acrius.That this our body's mortal frame

may know no sins, and fear no shame,

nor fire hereafter be the end

of passions which our bosoms rend.Ob hoc, Redemptor, quaesumus,

ut probra nostra diluas:

vitae perennis commoda

nobis benignus conferas.Redeemer of the world, we pray

that Thou wouldst was our sins away,

and give us, of Thy boundless grace,

the blessings of the heavenly place.Quo carnis actu exsules

effecti ipsi caelibes,

ut praestolamur cernui,

melos canamus gloriae.That we, thence exiled by our sin,

hereafter may be welcomed in:

that blessed time awaiting now,

with hymns of glory here we bow.Praesta, Pater, piissime,

Patrique compar Unice,

cum Spiritu Paraclito

regnans per omne saeculum.Most holy Father, hear our cry,

through Jesus Christ our Lord most High

who, with the Holy Ghost and Thee

doth live and reign eternally.

St. Dominic

Dom Alcuin Reid OSB

INTRODUCTION S PEAKING TO Benedictine Abbots in 1966, Pope Paul VI pointed to his Pontifical Letter Sacrificium Laudis of 15th August 1966 as an attempt to “safeguard your own ancient tradition and to protect your own treasury of culture and spirituality.” Sacrificium Laudis, addressed to superiors general of clerical institutes bound to choir, spoke of the need to preserve Latin in the choral office and warned: Take away the language that transcends national boundaries and possesses a marvellous spiritual power and the music that rises from the depths of the soul where faith resides and charity burns — we mean Gregorian chant — and the choral office will be like a snuffed candle; it will no longer shed light, no longer draw the eyes and minds of people. . Sacrificium Laudis went on to state that: The Church has introduced the vernacular into the Liturgy for pastoral advantage, that is, in favour of those who do not know Latin. The same Church gives you the mandate to safeguard the traditional dignity, beauty and gravity of the choral office in both its language and its chant. One suspects that Pope Paul VI would, therefore, be pleased that the increasing popularity of the traditional Benedictine office, and its retention or revival in a number of monasteries, now necessitates the reprinting of the Latin English Monastic Diurnal almost forty years after his (far too widely ignored and somewhat prophetic) warnings. First published in 1948 as an office book for Benedictine Sisters engaged in apostolic work away from their convents and for oblates of the Benedictine Order, this Diurnal went through five editions in fifteen years. Today, not only novices familiarising themselves with the Benedictine office and monks and nuns who are away from the monastery during the day, as well as Benedictine oblates, but also increasing numbers of the laity who wish actively to participate in the traditional Benedictine office in our monasteries where it is sung, or who wish to pray some hours themselves, will find this Diurnal to be an invaluable tool. This sixth edition is a reprint of the fifth, and may therefore be said to be covered by the imprimatur granted to that edition by the Bishop of St Cloud, Peter W. Bartholome, on October 4th 1963. The errors listed on the errata card included in the fifth edition have been corrected in the text. Otherwise, no change has been made to the liturgical texts or translations published in the fifth edition. However, the Preface, Introduction and the updated Table of Moveable Feasts (the kind assistance of the Saint Lawrence Press, UK, is gratefully acknowledged), may not be regarded as covered by the 1963 imprimatur, as they are new to this edition. A debt of gratitude is owed by all who use this Diurnal to its original compilers, Abbot Alcuin Deutsch (1877—1951) of St John’s Abbey, Collegeville, and the monks of his community. It remains to this day a testament to their pioneering devotion to the liturgical apostolate in the English-speaking world. May the availability of this Diurnal once again assist all who wish to draw from this treasury of Benedictine liturgical tradition and all who strive to observe the injunction of Saint Benedict to “put nothing before the work of God.” Dom Alcuin Reid OSB

The 6th or 7th Century. Attributed to St. Gregory the Great.

|

|