The Middle Kingdom

The gospel first arrived in the vast and powerful “Middle Kingdom,” or China, in the 6th century via Syria, with different emperors in turn permitting and suppressing the small community of faith planted there. Evangelization in the modern age began in earnest in the 16th century with the arrival of European missionaries such as the Jesuit Matteo Ricci, who painstakingly learned the language and customs of this immensely cultured people. By the 17th century, not a few Chinese had embraced the Lord Jesus Christ and his gospel. Over the next several centuries, they would testify to their commitment to him with their blood.

The protomartyr of China

The first Chinese martyr was in fact a Spanish Dominican friar, Fr. Francisco Fernandez de Capillas, who was captured in 1647 in Fu’an, in a wave of anti-Christian persecution. From prison, he wrote, “I am here with other prisoners and we have developed a fellowship. They ask me about the gospel of the Lord…. I live here in great joy … knowing that I am here because of the Lord Jesus Christ. The pearls I have found here these days are not always easy to find.” Those “pearls” were open hearts, people hungry for God. When, in 1648, Fr. de Capillas was beheaded, sealing the transformation of the Spanish priest into a Chinese saint, his spiritual children would show their worth. They followed him: 120 martyrs between 1648 and 1930, of which 87 were native-born Chinese Christians and 33 were foreign-born missionaries from various religious communities.

The soldier turned priest

In the late 1700’s, after the death of a number of Chinese lay catechists who refused to renounce the faith even under torture, a Chinese soldier experienced a turn of events that transformed him into the name and the face of a vast company of his fellow countrymen who had encountered the Lord. It happened that Zhao Rong was assigned to the company of guards sent to escort the French missionary, Bishop John Gabriel Taurin Dufresse, on the long journey to his execution in Beijing. There was something about this foreigner’s bearing, his patience in the face of suffering and imminent death, that struck the soldier. He began to listen to this leader of an outlawed faith. Soon, the soldier asked for baptism, taking the name Augustine. The foreign-born priest was killed, but he had a spiritual son: Augustine Zhao Rong asked for holy orders, becoming the first Chinese-born diocesan priest. In 1815, Fr. Augustine followed his spiritual father to torture and martyrdom.

“I am a Christian”

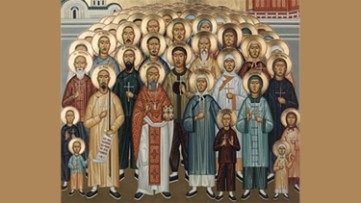

If the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church, as Tertullian stated in antiquity, the Church was taking deep root in this ancient land. Waves of persecution followed, each of which brought with it new martyrs, up through the anti-imperialist and anti-Christian Boxer Rebellion of the beginning of the 20th century. The foreign-born martyrs sealed their embrace of this land and people with their blood so completely that, like Fr. de Capillas, they are counted among the Chinese saints. The 87 Chinese-born martyrs were men, women and children – the youngest was 9 years old and the oldest was 79 – from all walks of life. They were Chinese priests who rose up in Fr. Augustine Zhao Rong’s footsteps, lay catechists, merchants, cooks, farmers, and an adolescent boy who, at the threat of being flayed alive, exclaimed, “Every piece of my flesh… will tell you that I am a Christian.” Many were offered freedom if they would apostatize, and refused.

There could be no greater proof that the Church was alive in China, or that the Lord had Chinese-born servants filled with courage and love. “Where I am, there will my servant be” (Jn 12:26), he had promised. This vast company of Chinese martyrs were with him, loving their Lord, their land and their culture unto the shedding of blood. Pope John Paul II beatified them together in the year 2000.

No comments:

Post a Comment